Here’s a storybook romance: the scholar and the outdoorsman, on their first real date.

She locks up the library at the stroke of 7:00 PM and hops into his pickup; they drive 50 miles out of town toward a pristine mountain lake. After cruising along the lakeshore for an hour or two, they come upon a rustic inn and settle in for a leisurely meal. They linger a while, sipping wine by candlelight, then walk hand-in-hand for miles along the water’s edge. When they’re caught in a sudden storm, he leads her to his cabin, builds a fire, and lays their clothes out to dry. As they gaze into the flames, she swathed in his old flannel robe, he leans in: but she blurts, “I’d better get home. If I’m not back before it gets dark, my dog will get anxious.”

And the reader violently shakes their head, looks back to the start of the paragraph, and starts counting on their fingers.

Slipping into the Future

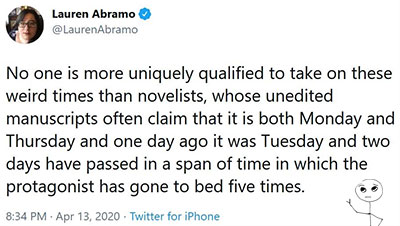

It’s easy for writers of fiction to lose track of time. I don’t mean time spent in the creative trance, but rather time that elapses inside the world of the story. A character might awaken on a Tuesday morning and end the day at a Saturday night fish-fry, or board an afternoon plane at LAX and step out into a New York sunrise. When they’re outdoors after dark, there’s always a full moon to light the way, no matter the hour or day. Or, as above, they might worry about getting home “before dark” when it must be already long after midnight.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your fiction writing.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your fiction writing.

The problem, I think, is that we authors get so focused on how events in our stories relate to one another—the sequence of action, or internal chronology—that we lose sight of external reference points. But our heroes live in a world, and despite all their antics, life goes on for everyone else. The sun rises and sets, the shops open and close. Keeping track of time means reconciling the activities of our characters with the big picture of our settings.

Over the next couple of months, we’ll look at ways that writers get themselves in temporal trouble and how to avoid it.

Unconsciousness as Stage Business

In theater jargon, “business” refers to some nonessential character action that gives visual interest to a talky scene or reveals a character’s hidden emotional reaction —lighting up a cigarette, for instance, or fidgeting with a prop. In prose, unconsciousness sometimes serves the function of stage business to cover a change of scene or a shift in perspective.

In theater jargon, “business” refers to some nonessential character action that gives visual interest to a talky scene or reveals a character’s hidden emotional reaction —lighting up a cigarette, for instance, or fidgeting with a prop. In prose, unconsciousness sometimes serves the function of stage business to cover a change of scene or a shift in perspective.

After an important story beat, the author may wish to halt the action briefly to give the reader time to reflect. And so we write, “He glanced at the clock. Midnight. He tumbled into bed, exhausted.” Or perhaps, “She felt the drug take hold. Soon, she felt nothing at all.” Whatever the means, the upshot is that the character starts the next scene with a changed outlook.

But while these sentences take mere seconds to read, in the world of the story you’ve taken a player off the field for four to eight hours. In a thriller, where the ticking clock drives suspense, that’s time you can’t spare. If your detective has just forty-eight hours to foil a bomb plot, he can’t pause for a nap every time he uncovers a clue. So what’s the fix?

Look for ways to shift your viewpoint character’s consciousness without obliterating it. One technique: subtly tweaking the narrative point of view. Let’s say you’re using a third-person limited PoV, filtering everything through the viewpoint character’s perceptions. Widening the focus gives both reader and character the distance to process an emotional beat and move on. Here’s an example:

He fell to his knees by the stream. His heart raced. Cupping his hands to drink, he saw them still spattered with the soldier’s blood; he plunged them into the icy water, scrubbing ‘til they were numb, then leaned back, panting raggedly. Far away, a cicada set up its unearthly shrilling. The sunlight through the leaves made rippling green shadows on the forest floor. When his breathing steadied, he set off again, following the current. Water led to civilization, he thought, and safety.

The viewpoint character starts the paragraph in a blind panic and ends it calm and determined, with a plan for survival. To make the transition, we zoom out of his head just a little. We’re still getting his perceptions, but his attention turns outward to his environment. His pause to reflect lets the reader do the same, and in just two sentences, taking perhaps ten seconds of in-story time, he’s ready to face what’s next, and so are we.

Using falling action for emotional effect is a pretty abstract concept, though it has concrete impact on the passage of time in your fiction. Next month, we’ll look at some more practical aspects of plotting that can scramble your timeline such as travel and distance, external events, and natural phenomena. See you then!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your fiction writing.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your fiction writing.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!