Last time, we looked at how English speakers’ agrarian past has left a lasting mark on the way we talk.

You might know the sensation of reading the novels of Jane Austen or William Makepeace Thackeray and feeling that you’re missing some important context because you’re unfamiliar with, say, the hierarchies of Anglican clergymen. In the same way, classic American works from Little House on the Prairie to The Grapes of Wrath assume a basic knowledge of agricultural practices that may be lost on today’s audiences.

Consider the verb “glean.” These days, it means to gather information bit by bit, but when it entered English from French in the fourteenth century, it had a very specific definition referring to the harvesting of grain.

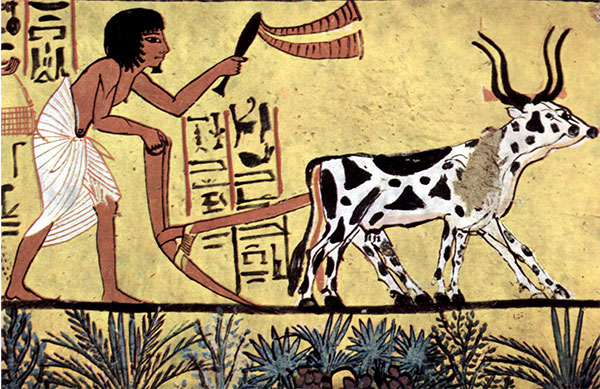

In those days, and for centuries afterward, barley, wheat, and rye were gathered in by reapers, who mowed down the stalks with large scythes and bundled them together into sheaves. In the process, some of the yield would inevitably be knocked from the stalks and left behind in the newly mown field.

Gleaners were a class of farmworker who followed after the reapers and picked up the tiny bits of grain they left behind. The work was backbreaking drudgery that demanded a keen eye, attention to detail, and great patience. As twentieth-century technology improved the efficiency of harvesting methods, the figurative meaning of “glean” came to crowd out the literal one, which survives now only as a historical curiosity.

A “farm” is a plot of cultivated land devoted to the raising of crops, usually of multiple varieties of vegetables, fruits, or non-food plants (e.g., flowers), which may be grown either for the farmers’ personal use or for sale. In addition to growing crops, farmers may also tend livestock, often non-grazing (e.g., pig farms, poultry farms) or those raised for their byproducts rather than their meat (e.g., dairy farms, sheep farms). Farms are often family-operated.

A “ranch,” by contrast, is not cultivated but made up entirely of wild pastureland. Rather than raising crops, ranchers concern themselves exclusively with animal husbandry, whether for meat (cattle ranches), fibers (sheep ranches), or other purposes (horse ranches). Of necessity, ranches tend to be far larger than farms and can be sited in less-fertile regions. Ranches may be family concerns, but the association is far weaker than for farms.

A “plantation” is definitely a family business. Properly speaking, the cultivated land is part of a larger estate owned by a single wealthy family who live in a large house onsite. But the owners do not themselves perform any actual farm labor; their role is as live-in managers or CEOs, while low-paid (or once enslaved) field hands tend the land. Plantations tend to be single-crop operations devoted to marketable products like tobacco, sugarcane, cotton, or coffee, and may encompass thousands of acres.

A “homestead” most closely resembles a mixed-use family farm in that it comprises tilled land, livestock, and living quarters. But the business model is very different; rather than raising crops or cash, the homesteader is focused on self-sufficiency, growing crops and rearing animals for personal use. Anything grown above a subsistence level may be brought to market or bartered for items they cannot fabricate themselves, but homesteaders aim to “live off the land” as much as possible. To that end, they might supplement their agricultural efforts by hunting game or foraging for wild foods in undeveloped areas on or near their property.

Finally, a word about “sharecropping.” Contemporary readers may understand the word to mean simply a poor or tenant farmer in the American South,” a full third of whom were Black and the rest White. But the reality of this economic arrangement was far more pernicious. Under this legal arrangement, a landowner “allowed” farmers to live on and cultivate small patches of land, growing a cash crop of the owner’s choosing. The owner would contribute all upfront costs, providing farmers with seeds, plows, mules, and basic housing.

To repay these debts, each farmer would give the owner a portion of the crop, as much as two-thirds, at the end of the growing season and was free to sell the remainder for cash.

But if the value of the owner’s share of the crop was not enough to cover the debt, the farmer would have to serve the landowner for another year. Creative accounting and shady business practices (Landowners often provided retail goods on credit as on the model of the company store.) left farmers in perpetual poverty with no hope of ever breaking out of debt.

Sharecropping was slavery by another name. Indeed, the practice became popular in the United States during Reconstruction, when it was one of the only options for formerly enslaved people to make a living and a way to continue to bring cheap labor into the country.

This brutally exploitative system persisted until 1966, when the US Congress passed a law officially abolishing peonage, or debt bondage.

That wraps up our look at the agricultural influence on our language, and with it, my series of blogs for the Proofreading Pulse. I’ve enjoyed the opportunity to talk with you about the quirks of the English language, strategies for better communication, and the writing life, but after twelve years and ninety-four posts, it is time for me to move on.

Thanks for reading, and remember: Words can harm or heal. Use yours wisely, and strive to tell the truth.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!