A while back, Julia H. wrote a post about the challenges of writing idiomatic English, particularly for non-native speakers. This time, we’ll consider a phenomenon that trips up even native speakers. Indeed, it has its origins in the spoken language and the imprecise way in which it sometimes translates to writing.

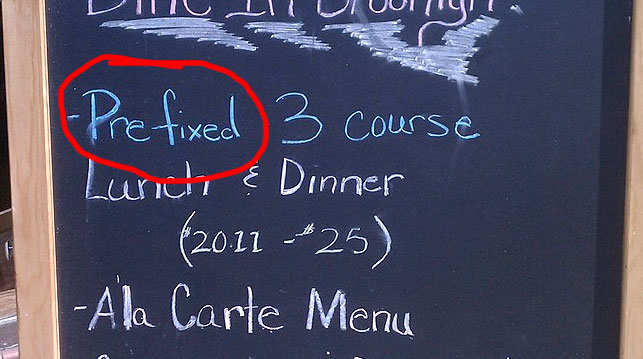

You may have heard somebody use the phrase “for all intensive purposes” when they meant for all intents and purposes. Such an error, which linguists call an eggcorn, usually occurs when the speaker has heard a phrase spoken aloud but has never seen it written out and so mentally substitutes something with a similar sound but a different meaning. A species of unconscious wordplay, eggcorns tend to be individual quirks; some, though, have become widespread in print, and a few have even started crowding the “proper” version of the phrase out of use.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your writing.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your writing.

Some of these phrases are nonsensical: “taken for granite,” for instance, for the proper taken for granted, or “duck tape” for duct tape. These don’t stand up to a moment’s consideration. What does assuming the truth of a statement have to do with hard decorative stone or a household adhesive to do with waterfowl? Usually, though, the new formation is at least plausible, with a little lateral thinking. The word “eggcorn,” which gives the phenomenon its name, is an approximation of acorn—that is, a big seed shaped like corn kernel, from which an oak tree grows in a process that could be compared to a bird’s hatching, if you’re poetically minded.

Thus, many eggcorns sort of make sense if you don’t think about them too hard. A rabble rouser stirs up the masses, and may inspire a rebellion; that doesn’t make him a “rebel rouser,” but you can follow the logic. A temblor is a geologist’s term for an earthquake, but its association with violent shaking causes many folks to transform it into “trembler.” Senile dementia is an ailment primarily of senior citizens, but it’s Alzheimer’s disease, not “old-timer’s disease.” And while age can also bring wisdom, oral legends from long ago are old wives’ tales, not “old wise tales.”

Many eggcorns replace a less familiar word with an everyday word. A foreign word might be partially Anglicized, as when the Italian espresso is mashed into “expresso.” An archaic phrase like bated breath—where “bated” is related to “abated,” meaning paused—may be imperfectly modernized to “baited breath,” which makes it seem as if you’ve got a trap in your mouth. That could make it hard to “bite your time,” but that’s all right; the correct form is bide, from the root word “abide.” Similarly, feats of derring-do might demonstrate a degree of daring (The words have the same origin), but the familiar idiom retains its old-time spelling.

When the sound-alike word gets close to the proper meaning but has a slightly “off” shade, some eggcorns achieve a strange poetry. A go-getter might achieve her goals, which makes her seem like a “goal-getter.” Buck naked seems like it should have “butt” in it, but it doesn’t, no matter what the rapper Ice-T says. (Speaking of which: that’s “iced tea,” not “ice,” please.) The female insect may prey upon her mate, but it’s a praying mantis because its front limbs look like praying hands. Likewise, an expatriate may still love their country of origin, even while living outside it; such a person is not necessarily an “ex-patriot.” Our vocal cords are like tautly stretched cables, but the musical association of “chords” proves irresistible; the incorrect version has nearly crowded the original out of print.

This is also the case with “If that’s what you think, you’ve got another think coming.” The idiom, which means “You’d better think again,” first appeared as early as 1897, but its humorous, purposely nonstandard construction has proved confusing to many writers and speakers, causing them to adopt the eggcorn “another thing coming,” which doesn’t make a lick of sense but is at least grammatically correct.

Figures of speech are inextricably woven into our daily conversational speech, but the eggcorn phenomenon shows that even fluent native speakers sometimes stumble over common English idioms. For this reason, academic writing styles, particularly APA, advise writers to avoid figurative or “poetic” language as much as possible. In an upcoming blog, we’ll look at some concrete strategies to help you do just that. In the meantime, if you’ve got a favorite eggcorn, let us know in the comments!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your writing.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your writing.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!