The future is urban.

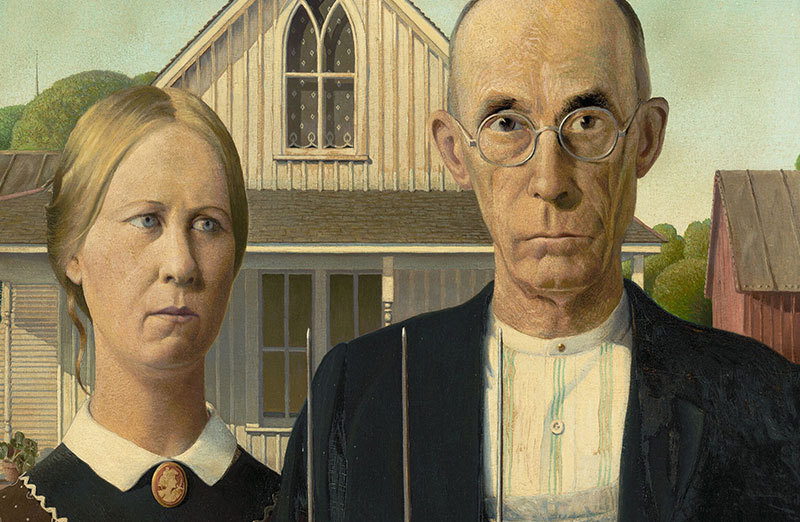

According to United Nations estimates, city dwellers became a global majority in 2007, and the trend has continued, with 57 percent of the world’s population living in urban areas as of 2024. In the United States, the divide is even starker; today, only 16 percent of Americans, fewer than one in five, live in a rural area. The number of Americans whose primary employment is farming has fallen too. From 1970 to 2012, their proportion dropped from 4.4 percent to just 1.5 percent of the overall population.

Agriculture has become far removed from the daily lives of most of us, but farming remains front and center in our idioms and expressions, just as important to the language as shipping and money. Modern English emerged in the fifteenth century, when daily life and economics in England, as in most of pre-industrial Europe, were overwhelmingly centered around agriculture. The English language as we know it developed and flourished in the countryside.

During this period, French was spoken at the royal court, and Latin was still the language of education and the legal system. The common people, such as farmers, gentry, and tradesmen, spoke various dialects that slowly coalesced into what we would today recognize as English.

English was a rustic tongue during its formative first four centuries, especially once it reached North America. It was the language of frontiersmen and settlers and backwoods people, those who scratched out a living from the land. And while the last 200 years have seen English take its place as the international language of money, science, and literature, our agrarian past has left a lasting mark on the way we speak: on our vocabularies and the idioms we still use even though we may have forgotten (or never known) their literal meanings.

In an agricultural society, weather, for instance, is a vital concern. A rainstorm could be a blessing or disaster depending on the time of year. Too little rain, and crops will wither in the field or fail to germinate at all, whereas too much rain will wash away the seed before it can take root. Thus, when trouble follows upon trouble, we say, “It never rains but it pours.”

One who brings good fortune, by contrast, is called a “rainmaker,” a word recorded in 1775 to mean a person who claimed the ability, via folk magic or pseudo-scientific methods, to produce rain in drought-stricken communities. By the mid-nineteenth century, the profession had become associated with scam artists and phony spiritualists, and the term was already starting to shift from its literal meaning to its current metaphorical one.

Another financial term, “windfall,” similarly has its origins in a weather event. Literally, it can refer either to fruit that has fallen from a tree to the ground, where it can be gathered without much effort, or to an entire tree that’s fallen down and can thus easily be harvested for timber. By extension, “windfall” is now used to mean a sudden financial gain, usually unexpected and unearned, such as a lottery jackpot.

And then there’s “Until the cows come home.” The exact genesis of this peculiar idiom, meaning “for a long or indefinite time,” remains murky. It was first coined by John Duton in his 1691 description of Ireland and later shows up in a British newspaper in 1829, where it is identified only as a Scottish saying. It makes sense on the most literal level; cows will habitually return from a pasture to their milking sheds at the close of day, but they are lumbering creatures, and will take their sweet time about it.

The image seems so weirdly specific that it’s tempting to speculate there’s some missing context at play, like a reference to some then-current event, some now-obscure play on words. All we know for sure was that people in Scotland were saying “till the cows come home” in the 1820s and other people throughout the English-speaking world adopted the phrase. That just how it happens sometimes.

Finally (for now, anyway), let’s consider “bumper crop.” You may hear this used literally, as to mean a large yield of zucchini from your garden, or metaphorically, to describe any unexpected abundance, as in “The year 1978 brought a bumper crop of classic disco records.” But what is the “bumper” in “bumper crop,” anyway?

Turns out it’s a metaphor on top of a metaphor. “Bumper” is an old term for a goblet of wine. Merriam-Webster locates it first use circa 1670. More specifically, it’s a goblet that is full to the very brim and on the verge of spilling. This meaning is likely related to the literal sense of “bump,” as in a bulge or protrusion, by way of fluid dynamics.

When you fill a glass to the top with water, and then keep adding water a drop at a time, you can observe a phenomenon called the meniscus, a dome of liquid that forms atop the column of liquid, extending a little above the rim of the glass. You can produce quite an impressive bump atop your glass before the surface tension breaks and the liquid spills over. (If you’re going to try this experiment in your own kitchen, keep a towel handy.)

And so the bump atop an overfull cup gave as the figurative “bumper” to refer to the cup itself, and then by extension a bountiful harvest, and then any great bounty. Why, it’s enough to make a fellow dizzy! (Or maybe that’s the wine.)

We’ll be back in sixty days with another look at agricultural idioms. Until then, may the holiday season bring you a bounty of joy and goodwill.

Jack F.

P.S. When you get back to work, ProofreadingPal is here to help!

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!