In the world of fiction, the narrator is not king, it’s God, and it rules over everything, even the author.

When we write, we act as God in the universes of our stories: creating and destroying our characters at will, judging and accepting, choosing cruelty and mercy. It’s quite the ego trip, really.

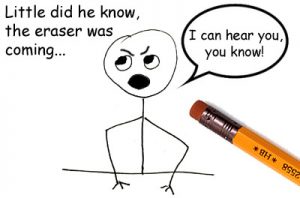

And so it can be quite the ego bruiser when we hand our stories over to the reader. Now, released from our minds (or rather, having escaped our minds via the words on the page), our characters live on in the reader’s mind, recreated by the reader’s imagination and subject to shared laws of language and culture. When the reader begins the story, the author is deposed.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Only the narrator maintains control over the story, dictating each word and determining precisely what is “on the page” and what is not. The reader’s imagination rebuilds the fictional universe only with the materials the narrator provides. (Indeed, when one reader’s interpretation strays too far from the story, other readers can cry foul: “That’s not what the story [meaning the narrator] says!”)

So it’s not an overstatement to say that, when a story changes narrators, one God is traded for another, one universe for another, and even one story for another.

If not handled with due care and respect, that transition can be more than a little jarring. In fact, if done poorly, changing narrators can bring the entire fictional universe to Armageddon (i.e., chaos, confusion, and the reader’s decision to stop reading).

An author who respects the narrator’s role can successfully change narrators, usually by giving each God its own territory. This could be done by separating them into different chapters or subsections clearly marked to warn the reader about what’s happening. A current example is George R.R. Martin’s book series A Song of Ice and Fire; a classic is Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.

An author who does not respect the narrator’s role will just jump around willy-nilly, telling us what various characters are thinking, adding the opinion of some all-knowing observer whenever and wherever, and generally muddling all sense of just who is telling the story.

Check out this example:

John felt all alone as he crept through the hall with his gun drawn, damp finger resting on the trigger guard. He thought the shadows ahead might be the branches of trees in the moonlight. Did one shadow hide the figure of his enemy?

I hope this guy knows what he’s doing. Coming up behind Joe with a knife in her hand, Jane snorted silently. She knew John had a lot of enemies, as many as the shadows in the hall before them.

Little did they know, the shadows were watching them.

There are five narrators crammed in there. At first, we’ve got a third-person narrator who only knows what John knows (call it John + 1). Then that narrator merges completely with John’s perspective (call it We-Are-John). Then we have Jane’s telling the story as inner monologue (call it I-Am-Jane). Then we have the third-person narrator again but from Jane’s perspective (call it Jane + 1). And finally we have an all-knowing narrator completely apart from either John’s or Jane’s perspective (call it Narrator + Shadows).

I n addition, there are four characters (John, Jane, an intrusive narrator who wants to give us a spoiler, and the shadows) and no sense of who’s actually talking to us. Five gods are fighting for turf and leaving the reader wondering what’s going on. If the speaker knows the shadows are watching John and Jane, then why does the speaker not know whether the shadows are hiding John’s enemy? And why are both John and Jane comparing the shadows to John’s enemies? And why would anyone want to read this?

n addition, there are four characters (John, Jane, an intrusive narrator who wants to give us a spoiler, and the shadows) and no sense of who’s actually talking to us. Five gods are fighting for turf and leaving the reader wondering what’s going on. If the speaker knows the shadows are watching John and Jane, then why does the speaker not know whether the shadows are hiding John’s enemy? And why are both John and Jane comparing the shadows to John’s enemies? And why would anyone want to read this?

I’m thinking we might get the idea that the narrator can jump around from movies, which cut from one character’s perspective to another’s and then to an overview of the action (with foreshadowing music) all the time. But although it may be tempting to think of the written narrator as the directing “eye” of the camera lens, the narrator is much, much more.

Yes, the director behind that camera lens controls a lot of our “imagination material,” but as the lens changes visual perspectives, we also have the continuity of actors’ portrayals, the same scenery, and the same composer’s score (or same producer’s soundtrack) cuing our emotions.

The narrator doesn’t just “show” the story; it doesn’t simply provide a window into another world. It is every person, place, thing, and abstraction in that world. It gives information for all our senses. It passes judgment on characters and tells us how to feel about them. It explains philosophies and provides insight. It decides what we can decide for ourselves and what is Divine Law. It doesn’t work with the characters as part of a team. It is every last word on the page.

Remember, the narrator is God. And a jealous God at that. If you don’t worship it properly, the narrator will smite your story Old Testament style.

Julia H.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!