I was catching up with a writer friend last week, and the conversation, as it usually does, turned to paying work: where it is and how to get it. My friend revealed that she had lucked into a side hustle writing paranormal romance, work that she found both fun and not too taxing, the latter because it kept to a pretty strict formula.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

When I refer to “formula fiction,” it’s not a disparagement but a statement of fact. Many popular fiction genres are written to rigid specifications. By publisher mandate, every romance novel must have a happy ending, and many imprints specify X number of sex scenes and Y number of misunderstandings between the main couple; house style may even dictate where in the word count those scenes must fall.

Series fiction, from the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew books many of us devoured as young readers to the paperback adventures of Nick Carter or Mack Bolan, ring only minor changes on a set template from book to book; the army of pseudonymous authors who worked on the Hardy Boys and other associated series were even contractually obligated to include a set number of jokes in each chapter.

Formula fiction may have a bad critical reputation, but then, so do chain restaurants, but you can get a nutritious meal there regardless. The draw is consistency. Some books that follow a given formula will be better than others, but so long as the formula is one you enjoy, even the worst of them will still be pretty fun.

Indeed, America’s most globally dominant cultural product of the last fifteen years, the Marvel movies, are made to a rigid formula that determines with algorithmic precision the length and placement of their action sequences, character beats, and quips. The quality of the individual installments varies but is never less than workmanlike; there’s always plenty to like, if you like that sort of thing.

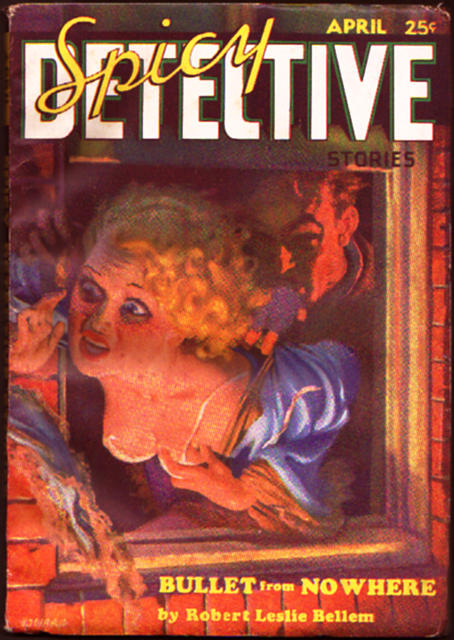

There has always been an audience for formula fiction, and perhaps never more so than in the heyday of the pulps. These magazines, which flourished in the first half of the twentieth century, were printed in small type on cheap paper, which gave them their name. The more reputable “slick” magazines like Collier’s or The Saturday Evening Post featured fiction too, but the pulps were populist entertainment aimed squarely at working people.

Every month, you’d get a fistful of new stories in popular genres (westerns, mysteries, romance, science fiction, adventure) all for a dime in a compact format you could roll up and stick in your pocket. It was value for your money and very good business. At its peak in 1929, the detective pulp Black Mask was selling about 120,000 copies per issue. For comparison, that’s on a par with sales of The New Yorker or The Atlantic during the same time period.

One pulp hero who’s had an unexpectedly long afterlife is Doc Savage, “the man of bronze,” a globe-trotting adventurer whose mind and body had been developed to the peak of human perfection; the character was an avowed inspiration for Superman. Doc Savage’s self-titled magazine debuted in 1933, ultimately running for 16 years. Each issue featured a lead story the length of a short novel or long novella. In 1964, Bantam Books began republishing the stories as a series of slim paperbacks, and throughout the 1970s and ‘80s Doc Savage was a staple of drugstore spinner racks and used-book stores. The character has remained popular ever since, mostly in comic books.

As with other pulp characters like the Shadow or the Spider, the writing of Doc Savage’s adventures was credited to a “house name,” a blanket pseudonym (in this case “Kenneth Robeson”) that fostered the illusion of a single creator even when multiple writers were needed to churn out as much as 50,0000 words, month in and month out. Doc was unusual, though, in that the vast majority of his adventures, 159 of the original 181 stories, are indeed the work of a single man, Missouri native Lester Dent, one of the most prolific writers of the pulp era.

Besides the two-fisted super-science of the Doc Savage stories, Dent wrote in a variety of other genres, including mystery and detective stories, westerns, sea stories, and jungle adventures. His stories are rife with sunken treasure, lost cities, exotic poisons, clever gadgets, and larger-than-life heroes and villains, all the stuff calculated to thrill the twelve-year-old boy I was when I discovered his work and all of it produced with blazing speed and very little rewriting.

He accomplished all this by working to a set of structural guidelines, what he called “The Lester Dent Pulp Paper Master Fiction Plot.” It’s a simple series of lists and checkpoints, equally applicable to a novel or short story, which can reliably guide you through from the start of a manuscript to its completion. In the next installment of this blog, we’ll break it down step by step and unpack how Dent’s master plot can be applied across a range of fiction genres. See you then!

Meanwhile, did you know we’re available to help you develop your fiction here at ProofreadingPal? And be sure to check out ProofreadingPal’s offer of a free sample edit.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!