This blog post concludes our series on the precepts of the federal Plain Writing Act of 2010 and how you can use them to improve your own writing. We end with a topic that most of us never consider in our day-to-day communications but which can be fantastically useful for improving the clarity of your message: testing your work.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

You can find more about the nuts and bolts of testing in Section V of the guidelines associated with the Act; in this post, we’ll ask the broader questions of when and why it’s important.

Those who work in marketing and related fields might be familiar with A/B testing, sometimes called “split testing.” The principle is simple: When you’re faced with a choice between two options, try both and see which one works better.

In practice, let’s say you’re designing a product advertisement and there are two potential slogans. To test them, you would mock up multiple ads, identical in every way except for the slogan, show them to people (the more people, the better), and ask their opinions.

Or maybe you’re part of a team building a webpage for an e-commerce site, and there’s disagreement among the developers as to where the “Buy” button should sit on the page. You would build several sample pages, all alike except for the location of the button, and gather feedback from test users to determine which gives the best outcome. Then you would implement that design on the live site.

These tests are, literally,* experiments. A/B testing represents the application of the scientific method to problems of writing and design. In the laboratory or in a focus group, experimenters change isolated variables in a framework that otherwise stays the same, and then collect data by observation. The robustness of the results is measured by their ability to be replicated.

Testing and experimentation help us make decisions based on facts rather than instinct. We all have biases. A web designer may have strong feelings about where the “Buy” button should go, and an advertising copywriter may be particularly fond of their clever wordplay in one of those slogans.

Naturally, in many kinds of writing, both everyday writing like a to-do list or a personal letter and creative projects like a poem or story, our instincts are perfectly serviceable guides. Can the passage be understood? Is it aesthetically pleasing? Have you expressed yourself as you wished? In such cases, focus grouping is unlikely to improve your work, and may even make it worse; it’s a withering insult, after all, to say a literary work reads as if “written by committee.”

But there are different aims for different kinds of writing. For a poem or novel, it’s OK, even expected, for the reader to bring themselves to your work, to sit with your words and take an active part in constructing their meaning.

Other projects, however, such as government documents, instructional and educational materials, and advertising, are far more purpose-driven. There is a single, clear meaning for the reader to take away: a useful piece of information, a recommended course of action, even a simple imperative like “buy.” And if the text doesn’t deliver that meaning, then that text has failed.

It goes back to the core principles of plain writing: users must be able to find, understand, and apply the information they’re seeking. Now, you might have a good eye for clear, actionable prose, but you too have your biases, like everyone. So, given the stakes, your success in hitting those goals must be proven by data.

(I should note this is also where a good editor can help. Try ProofreadyingPal here for free!)

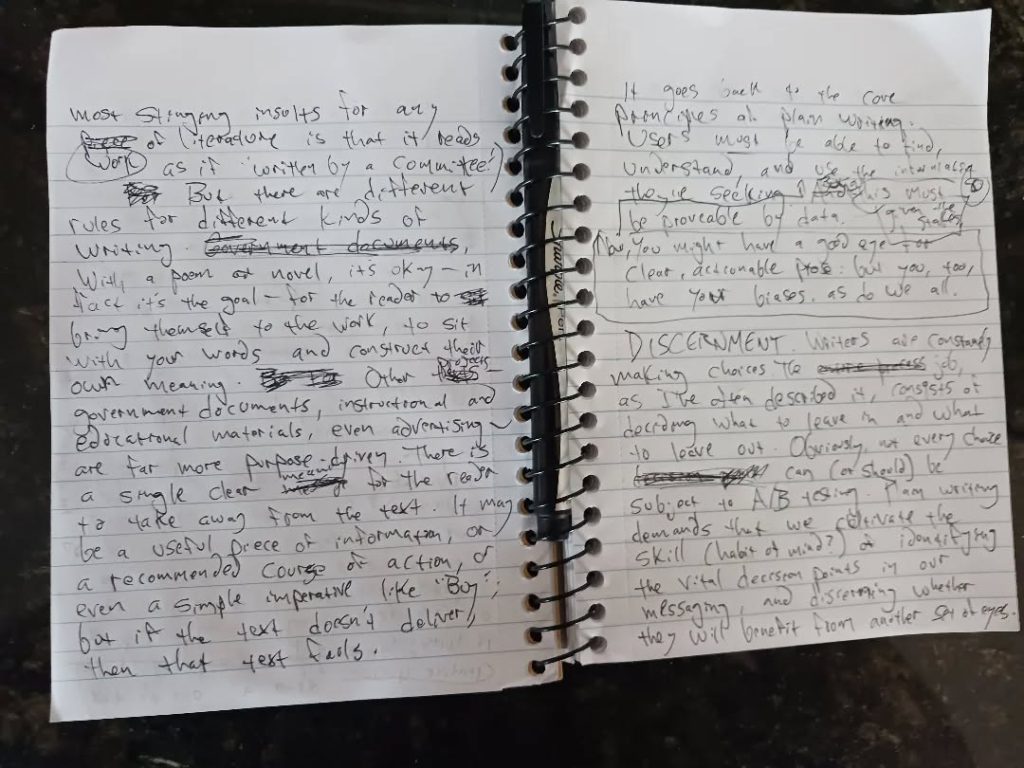

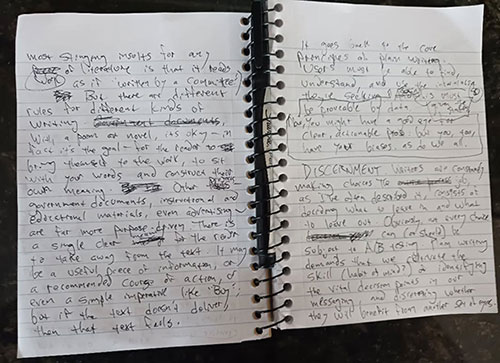

Writers are constantly making choices. The job, as I’ve often described it, consists of deciding what to leave in and what to leave out. Look at this photograph of the notebook in which I drafted these last few paragraphs. Every scratch-out, every circled phrase, every arrow and insert represents a point at which I changed my mind about a choice I’d made.

Obviously, not every choice can (or should) be subject to A/B testing. Plain writing demands that we cultivate the skill, or the habit of mind, of identifying the vital decision points in our messaging and discerning whether they will benefit from a fresh set of eyes or a survey of outside opinions.

That all begins with having a full understanding of your goals for a given piece of writing. Optimizing your message for the best outcome depends to some extent on what your desired outcome is, whether commerce, engagement, page views, activation, or knowledge retention, it always begins with a dedication to usability.

Which brings us full circle, in a way, to the first precept of plain writing: know your audience and anticipate their needs. It’s a different model of writing from the one to which we may be accustomed. It’s not about self-expression, and it’s not a vehicle for showing off your exquisite sensitivity or your novel perception of the world; it’s something far more radical than that: a model of writing as service, as a way of doing good for others.

By helping you communicate with according to your readers’ understanding, writing plainly demonstrates that you care enough to do the job right.

Jack F.

*Correct use of term “literally.”-editor

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!