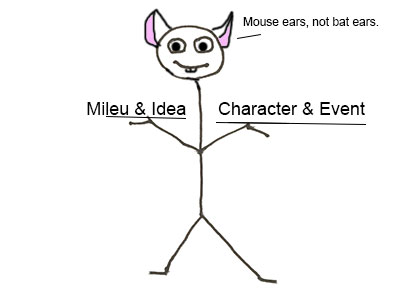

We’ve spent the last several blogs talking about narrative structure, particularly about writing beginnings and endings in the context of four frameworks: milieu, idea, character, and event stories. Now, we’ll put this theoretical model into practice.

Putting It All Together

First, it’s important to remember that these structures are archetypes, meaning that you will almost never encounter a “pure” example in practice. The most tightly plotted idea story may feature character beats on its way to answering its central question; the most exhaustively imagined milieu story may include mysteries to be solved.

So given that two or more of these aspects may occur in the same story, the best working structure for the story is determined by the ratio of milieu, idea, character, and event elements present therein, sometimes called the “MICE quotient.” When a single thematic element predominates in a story, it suggests a particular narrative structure. When the ratio is more balanced, things can get tricky.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

Let’s examine two well-known works of speculative fiction as examples. We’ll be looking at important plot points, so spoiler warnings apply.

1984

George Orwell’s novel, 1984 (published in 1949), tells the story of Winston Smith, a citizen of an authoritarian state. Winston’s homeland, Oceania, is the most infamous dystopia in literature, a nightmare of surveillance and paranoia. The all-powerful Party seeks to eradicate even freedom of thought; the authorities literally rewrite history and bombard the citizens with propaganda, undermining the possibility of objective truth beyond the diktats of the state. Winston yearns to escape this enforced conformity, but his efforts to free himself prove futile. Betrayed by his supposed friends, his spirit broken by torture, he is reduced to a ruined shell, pathetically grateful to the state for sparing his life.

1984 operates in multiple modes. The novel is as concerned with the political environment of Oceania as with its characters, and could fit comfortably into the category of milieu story; although this story type usually requires an outsider as a viewpoint character, Orwell sidesteps this by having Winston Smith, newly conscious of the systems of oppression surrounding him, examine his world as if for the first time, thus filling the role of the “stranger in town.” Winston’s rebellion is a threat to the status quo, and his sexual relationship with Julia upends his own life, marking the book as an event story. And there are mysteries hanging over the novel that suggest an idea story structure.

1984 is all of these things in equal measure. Structurally, however, it hews closest to a character story, beginning precisely when Winston decides to try to change his role in the world, going from a cog in the system to a secret rebel, and ending when that attempt fails. Such is Orwell’s genius, though, that he sustains all four threads throughout the novel and ties them together in the climax; the answers to all mysteries, Winston’s growing love for Julia, any possibility of leaving his environment, his attempt at redefining his character: all these tensions are resolved behind the doors of Room 101.

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”

1984 is an exceptional work; most stories that play in multiple modes tilt far more obviously to one or the other. Ursula K. LeGuin’s award-winning short story (published in 1974) is one such multivalent work, another story of an imagined society, albeit one very different from Orwell’s Oceania.

Omelas is a city-state of beauty, high culture, and plenty, without exploitation or greed. Its people are happy and virtuous. Many specifics of daily life are left to conjecture, or more properly, to the reader’s imagination, but the narrator paints a picture of an ideal society before revealing that Omelas’s good fortune is purchased by the misery of one small child. This wretched victim is the necessary sacrifice to maintain the prosperity and happiness of the whole city.

Each citizen of Omelas learns of this awful bargain upon reaching adolescence, and almost all come to accept it, in time. But there are some (the narrator tells us) who refuse to live with the price—who turn their backs on Utopia and search for something better.

LeGuin’s fable could easily have been framed as a milieu story; it’s easy to imagine a version of the story structured around a visitor to Omelas exploring the place, partaking of its delights, and at last discovering its secret. Or it could have been a character story, following one young inhabitant’s journey from innocence to experience as she learns the price of her city’s happiness and struggles to respond, culminating perhaps in her decision to leave home.

But as it stands, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is an idea story through and through. It is a metafiction—that is, a story that acknowledges its own status as a fictional work. The narrator reminds us continually of her choices of what to include and what to omit, and frets that some detail may seem unconvincing. It’s posed as a thought experiment—an invitation to imagine a utilitarian utopia, based around the greatest good for the greatest number, and then ponder its ethical implications. Stories of all types may center on such thought experiments, of course, but LeGuin chooses to put her agenda front and center here, and to focus entirely on moral question without superfluous incidents or character moments.

Putting the Ratio to Work

Now, it’s one thing to analyze a finished story and work backwards to determine which structure it follows. That’s the job of a literary critic. But understanding the MICE ratio can also be useful when you’re in the midst of writing, especially when you find yourself stuck, or are unsatisfied with your completed first draft. Next month, I’ll show you a low-tech trick that can help you find the best shape for your story and get it moving forward again. See you then!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!