In previous posts, I’ve written about several types of logical fallacies, or false logic, that people use in their writing and speaking to convince readers and listeners and how to avoid them yourself. An additional logical fallacy I’ve noticed a lot recently is post hoc, ergo propter hoc. Translated from the Latin, it means “after this, therefore because of this.” Put another way, this fallacy occurs when an argument consists of the following: something (A) was caused by something else (B) only because B came after A. Here are a few simple examples:

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

In all of these cases, it may be that A had some causal effect on B. It is possible that the medicine in the first example helped lead to the healing. In the second example, perhaps the actual work of the new president truly made a difference in stock market performance. A little less likely (unless you happen to believe in old wives’ tales about getting too cold making you sick), perhaps the snow in the third example pushed someone over the edge into illness territory. But the only thing certain in all of the examples is that the first thing preceded the second in time.

We see this type of argument all the time in the news, and I’ll discuss a few famous examples of cases of post hoc, ergo propter hoc in today’s post and how to avoid blindly believing arguments without truly understanding them and their potential for falsehood.

Few people, if any, like to shell out more money for the goods and services they need to sustain life, and it’s indisputable that prices have risen due to the rise in tariffs on imports. One argument for these increased tariffs is based on reported economic growth of the late nineteenth century following a period of increased tariffs. What this argument fails to point out are the other factors in this perception of overall growth: “labor force expansion and capital accumulation.”

My own children are sixteen and nineteen, so it seems at this point ages ago I was considering those initial rounds of vaccines recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, and I do recall people telling me to skip the vaccines to avoid a future autism diagnosis. This argument has since been proven false, as despite the fact that autism diagnoses often come about around when initial rounds of vaccines are given, the timing of the diagnosis is related to the timeline of childhood development, which happens to correspond the the timeline of recommended vaccine administration.

This argument led to a lot of vaccine paranoia beyond MMRs and autism, namely, that rather than solving medical problems, vaccines cause medical problems, a huge concern for the medical profession in its attempts to work for public safety and combat misinformation.

The medical field is especially prone to confusion based on post hoc arguments. People looking to cure or avoid serious and even life-threatening illnesses are always looking for evidence to support a plan to obtain or maintain better health. A number of years ago, it was reported that carb-rich diets had been linked to higher rates of lung cancer, but in this as many cases this “finding” was eventually shown to be based on “case-control studies looking at multiple factors and finding small associations”—basically pointing to a small factor when it’s not the true cause.

So how’s a person to know when they are presented with a post hoc argument? One sign is when an argument is presented as an absolute statement. Indeed, an absolute statement should raise your alarm, as words like “always,” “in all cases,” and “without exception” are often used when there’s a lack of evidence to support a convincing point.

Another thing to note when considering this fallacy is whether there is actual evidence bridging the connection between point A and point B. If the argument is presented as absolute and without accompanying evidence, it’s time to start asking some questions.

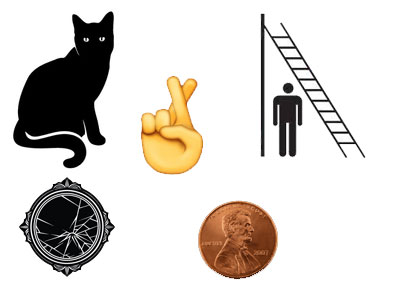

The post hoc fallacy is all about blurring the line between simple chronological correlation and actual causation. Note that almost all superstitions rely on this fallacy. “I found a penny and picked it up, and all day long I had good luck” implies the penny caused that good luck, but that’s all it is: an implication. Without evidence, that’s all it can ever be.

Finally, consider whether an argument is post hoc when other causes may have been ignored. Looking again at an example from above, “My best friend took this medicine, and now he’s all better,” what if in addition to taking the medicine, your friend also lay in bed for three days, stayed hydrated, and rested? Starts to seem a little less convincing about that medicine when other factors are taken into consideration.

The bottom line: When presenting an argument, avoid absolute statements linking events or facts without appropriate connective evidence, and when receiving an argument, start asking questions when you suspect the causal relationship may be false.

Sarah P.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!