In a recent blog on using vertical lists, I touched on how a list can embody what I call the “organizational principle” of a piece, or how a list can provide a miniature rundown of an essay’s content. I want to expand upon that idea here because it has important implications for your writing. We’re not so concerned here with formatting lists within a piece of writing; today, let’s focus on the pre-writing phase of your project and how list making can be a useful method for organizing your words, and with them your thoughts.

Going Deep with Nested Lists

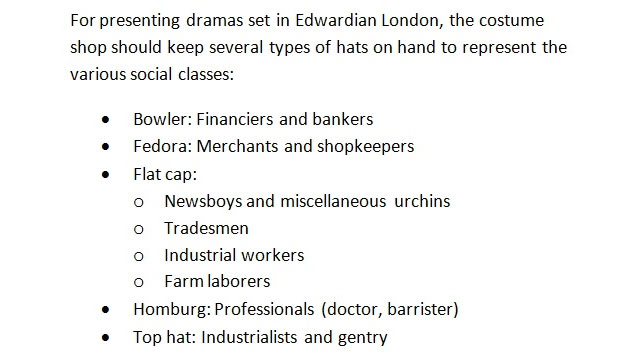

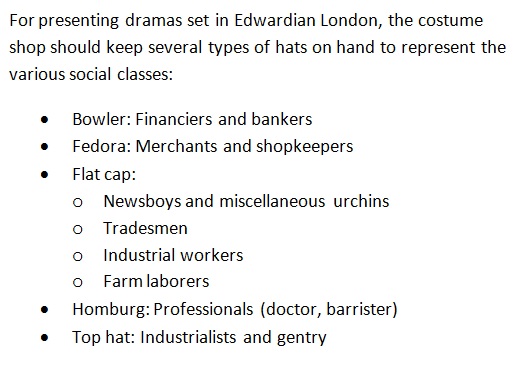

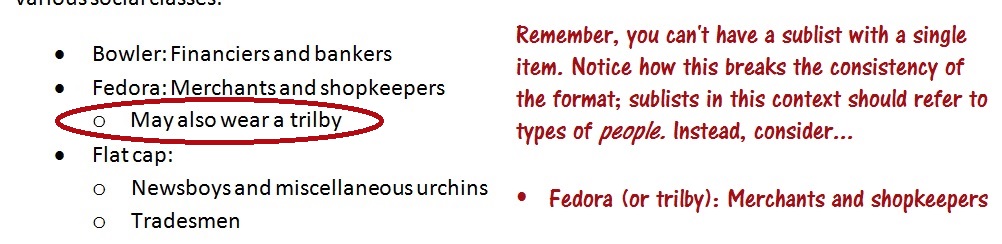

The art of crafting an argument consists of stating a general point, and then bolstering it with supporting details. You may repeat this process several times, depending on the complexity of your argument—as many times as necessary to make your case—but each time the progression is the same, from the general to the specific. Writing instructors often call this drilling down. When writing a list or an outline, we call it nesting. Here’s an example of an unordered vertical list with a nested secondary list, called a sublist, which is indicated by a further indentation and different style of bullet.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

The word nesting may conjure up images of those Russian dolls that stack inside one another, each breaking open in turn to reveal a smaller replica of itself. With lists, though, each level of list and sublist must have at least two items.

The word nesting may conjure up images of those Russian dolls that stack inside one another, each breaking open in turn to reveal a smaller replica of itself. With lists, though, each level of list and sublist must have at least two items.

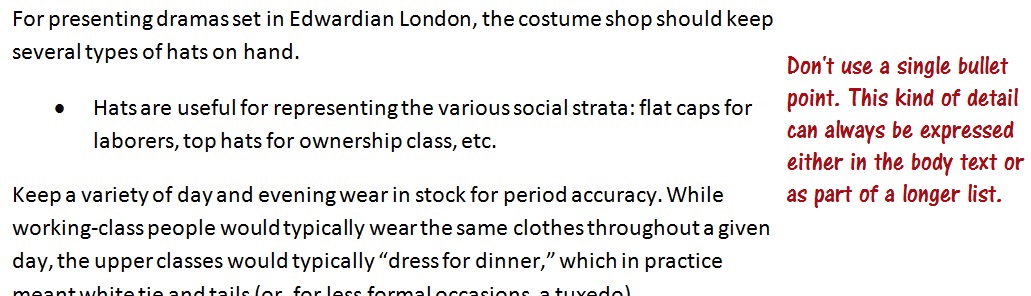

Singles Barred

Let me say that again plainly: every list must have at least two items. This may seem so obvious as to be hardly worth mentioning, but it’s an error we see frequently in our work for ProofreadingPal. It’s especially common at the outlining stage, and we’ll talk more about that below. But we’ll occasionally see it in a vertical list in the body of a paper, usually when there’s some bit of additional information that doesn’t seem to fit into the body of the text. If the topic does not warrant at least two items, consider whether it should be included at all; if so, look for creative ways to incorporate it into the main text.

Sublists too must have at least two items; if you find yourself with a sublist with only a single item, either omit that fact or find a way to work it into the main list as an exception or parenthetical aside.

Note that even though each list must have at least two items, not every set of two items will require a list. Take another look at the list above. Each of the five items includes at least two examples, but only one is broken down into a sublist. In the remaining items, the examples (e.g., bankers, financiers) are sufficiently similar in concept that they require no further distinction. “Flat cap” is the exception because the wearers may be either children or adults, urban people or rural, poor or middle class. There is enough variety among these walks of life to warrant a detailed breakdown.

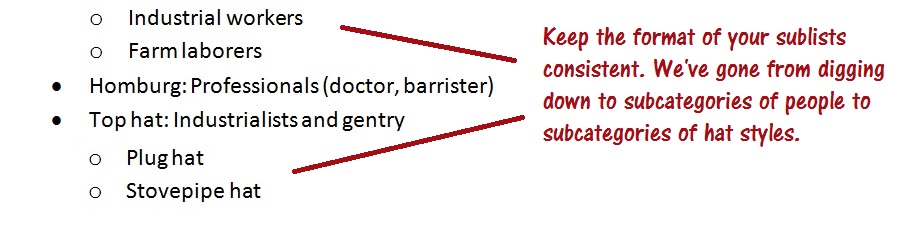

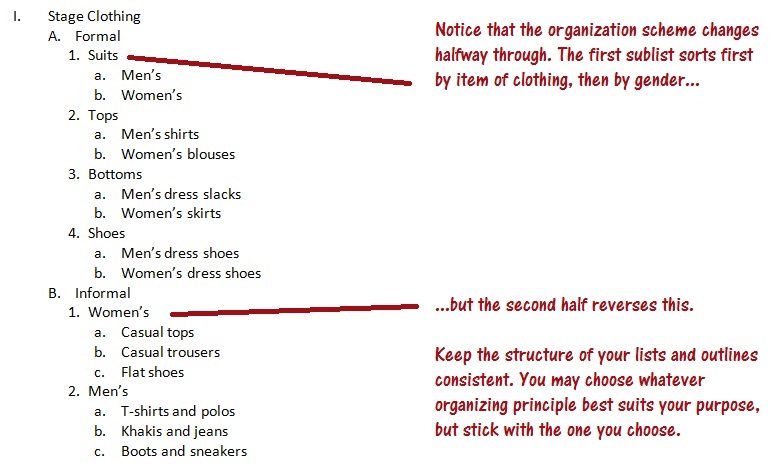

For logical flow, keep the structure of the list consistent. The criteria that define a new item or sublist should be the same from start to finish.

Tracing the Outline

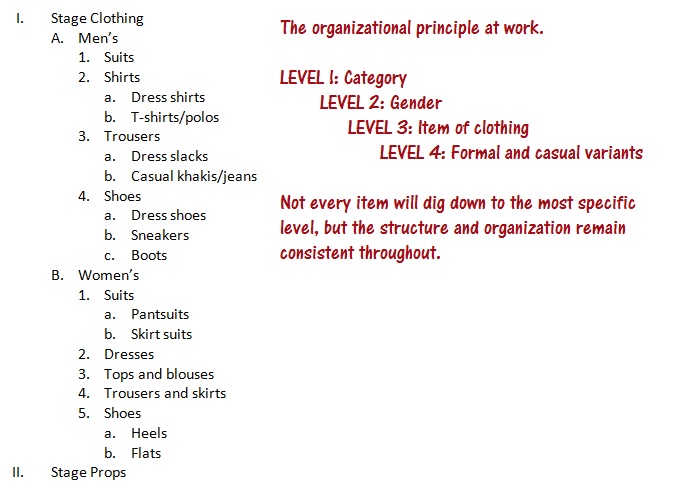

You probably learned about outlines in high school. An outline is simply a specialized form of list used to organize the flow of a piece of writing. Outlines can go several levels deep—as many levels as you need for the appropriate degree of detail—but no matter how deeply you go, you must always be able to find your way back to the main thrust of your argument.

Because of this, outlines are widely used in all types of writing. An author might plan a novel or screenplay by using an outline, while an academic may use one to plan anything from a simple essay to a doctoral thesis. (For academic writers, referring back to your outline will also help you assign the proper heading style to the various sections of your paper.)

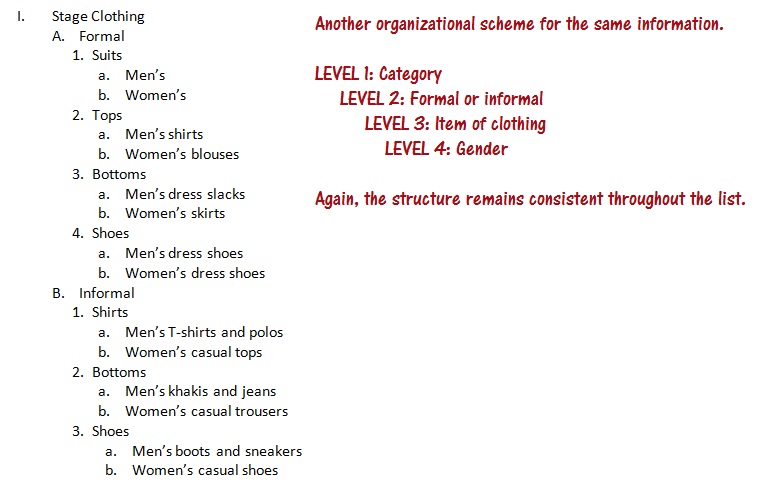

This example shows how outlining can help you drill down from the general to the specific.

There’s no set way to compose an outline. In some cases, a single organizational principle may suggest itself; other times, you’ll have a choice of workable options. Planning with an outline allows you to try out different structures before committing to one, which might save you time rewriting later.

The standard rules apply; whatever organizing principle you choose, it must remain consistent.

Now that you understand the theory, my colleague Julia has written an outstanding article that will walk you through the process of constructing an essay using an outline as your blueprint.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!