Longtime readers of this blog will know from my post, “The Writer’s Bookshelf,” that I keep my desk stocked with resources for writers. Many of these focus on the technical side of things, but I have a special weakness for books about the art and science of storytelling. I’ve accumulated (“collected” sounds too systematic) a shelf-load of these how-to books. Some, like Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, are largely autobiographical, whereas others, like Kit Reed’s Story First: The Writer as Insider, are dry and theoretical. Most are somewhere in between.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

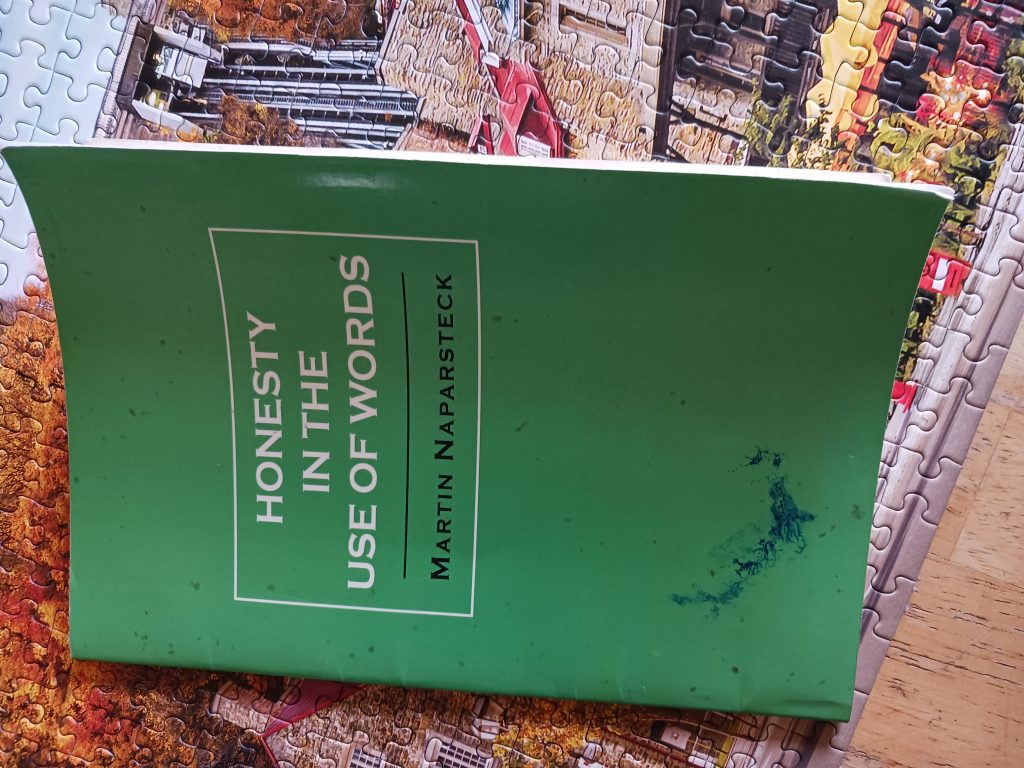

I’m always on the lookout for this kind of thing while browsing at my local used bookstore and was recently delighted to find on the dollar table a curled, ink-smudged copy of Honesty in the Use of Words, a monograph by Rochester-based writer and teacher Martin Naparsteck. A self-published pamphlet, Honesty in the Use of Words comes out swinging with its mission statement: “Competent writing is a skill. Good writing is an art. Great writing is an act of high morality.”

How could I refuse?

In casting truthful writing as an ethical duty, Naparsteck offers not just an instructional guide but something close to a manifesto. He leads with a provocative thought exercise.

Which of the following is a better piece of writing?

A. Araham Linkon were ta 16th prez of the u. States.

B. Abraham Lincoln was the 15th president of the United States.

Naparsteck contends that Sentence A is objectively better because it is factually accurate while remaining, despite its spelling errors and idiosyncrasies, perfectly understandable. Sentence B has the advantage in spelling, grammar, and capitalization but fails overall because the information it delivers (the very reason for writing it in the first place) is inaccurate.

We should always strive to write prose that is both correct and true, of course. Truth is no use to anyone if it cannot be plainly understood, and grammatical prose, being based in how the majority of those who speak the language use the language, is more universally comprehensible than nonstandard constructions like Sentence A. But if for any reason you are forced to choose, Naparsteck argues, you have a moral obligation to tell a rough truth over a smooth lie.

And you are forced to choose, constantly and often without even realizing it. Every time you use a euphemism or a cliché or pass over an awkward-but-accurate term in favor of a better-sounding word that’s “close enough,” you stray from the truth. Every time you commit a logical fallacy, repeat unsourced anecdote or so-called “common knowledge,” or parrot conventional wisdom without subjecting it to critical analysis, you risk spreading a lie.

And when you fail to do comparative research to confirm the accuracy of your information against multiple sources, you increase the likelihood that untruths will slip through.

My copy of Honesty in the Use of Words was published in 2005, long before the widespread use of generative AI, but the book seems prescient on that score. As we’ve noted in “AI Reconsidered: Beyond the Hype,” these large language models have no means to distinguish truth from untruth but only to assemble words in ways that are statistically likely. They are thus likely to produce passages like Sentence B: grammatically correct, confidently stated, and wholly wrong.

Given the unchecked spread of this slop across the web, any electronic source must be regarded as suspect, and cross-checking sources is more important than ever.

Naparsteck gives plenty of actionable advice on research and identifies a number of rhetorical devices that can short-circuit critical thought and lead to inaccuracy, but his higher purpose is to make an argument for honest writing as a civic virtue. In this regard, Honesty in the Use of Words invites comparison to George Orwell’s 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language,” which Naparsteck cites as an inspiration. Telling the truth, he argues, is essential to living a functioning democracy.

This message too is particularly suited to the current historical moment. There’s a sense of moral outrage that drives the book. It’s fueled, one suspects, by its author’s experiences during the Vietnam War and the national trauma of Watergate, in which the US government displayed little concern for the truth in its dealing with citizens.

We need that same outrage in today’s climate of deceit, where the truth is dismissed as “fake news” and blatant lies aim not to persuade but simply to assert dominance, all to demonstrate that truth itself is secondary to the exercise of power.

But by its nature, truth is always relevant. And like it or not, the truth of your writing is your own responsibility.

ProofreadingPal’s suite of services are those of editors, not fact-checkers, and so does not include verifying your work for accuracy; occasionally we’ll flag an obvious factual error, but as a general-purpose service we mostly limit ourselves to grammar, syntax, logic, and usage.

ChatGPT and its ilk cannot distinguish truth from falsehood. And even magazines and book publishers are phasing out the profession of fact-checking, throwing that task back to authors.

If writing is the art of making choices, our first priority must always be to tell the truth. Journalist Maggie Kuhn tells us, “Speak your mind, even if your voice shakes.” Write honestly and accurately, to the best of your ability. An editor can help fix the grammar afterward: but the truth of it, that part must come from you.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!