Novelist and playwright Peter De Vries (1910–1993) is reported to have said, “I love being a writer. What I can’t stand is the paperwork.” De Vries was one of America’s foremost satirists, and the sting of the line comes in how it pokes succinct fun at the arrogance, laziness, and entitlement of would-be writers.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

That’s why, as an editor, it’s been so disheartening to see the emergence of a technological product that panders so nakedly to those human failings. Generative predictive text (GPT)—often inaccurately called “artificial intelligence”—promises to churn out persuasive or informational text to the user’s specifications based on only a brief set of prompts; that is, to let the user “be a writer” with the sometimes tedious “paperwork” of, y’know, actually writing.

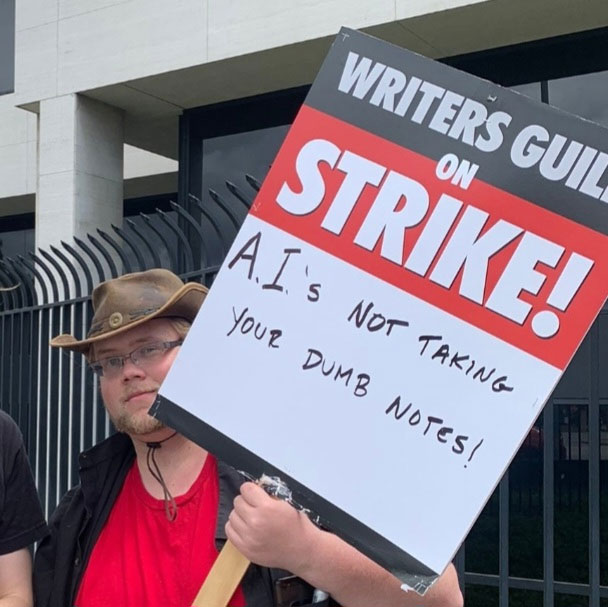

But it gets better (by which I mean worse). Having already erroneously sold GPT as a substitute for doing research, developing a thesis, picking your words, and putting them in order, tech entrepreneurs are horning in on the one part of the process that still ostensibly requires a human touch: criticism.

To be clear, I’m not talking about services that check your work to avoid plagiarism; that’s basic pattern recognition, and sifting huge volumes of text strings at blinding speed is a task ideally suited to a computer. No, the business model here is to replace a human being, one who will read your work and offer an informed opinion, with an algorithm that scores your writing on metrics of readability and even “vividness,” using data analysis.

This was the sales pitch for Prosecraft, a start-up that made headlines in the literary world in the summer of 2023. Marketed to fiction writers, Prosecraft was in some ways a souped-up version of the Editor function on the Review tab in MS Word. Upload your text, and the site would display a word count, a statistical breakdown of active vs. passive voice constructions, and a full count of all adverbs, those ending in –ly and otherwise. It could also generate a brief plot summary, which is genuinely impressive.

A bit more dubiously, the site also purported to rank the zing of your writing based on the absence or presence of certain words that had been assigned varying degrees of “vividness.” And in that ranking function lay the problem. Prosecraft allowed users to compare their own work to snippets from commercially published books in its dataset—about 27,000 books, in fact, including novels by big names like Stephen King, Jodi Picoult, Celeste Ng, and J.K. Rowling.

It’s arguable that the snippets themselves were presented in an educational context for noncommercial use (Prosecraft was a free service.), making them permissible under the “fair use” provisions of US copyright. That was the argument put forth by Prosecraft’s creator, Benji Smith, and it might have held water but for two facts. First, Smith admitted that he had not actually purchased those 27,000 books by legitimate means but had torrented them from pirate sites.

Secondly, Prosecraft was only a sideline to Smith’s major business venture, a paid subscription site called Shaxpir (pronounced—sigh—“Shakespeare”),

an online word processor that promises to use machine learning to “help authors write better books” by improving their prose styles and crafting more effective emotional arcs. Shaxpir proudly claims that the natural-language algorithm it uses to evaluate prose quality or emotional impact derives from “a giant linguistic model of literature” created by analyzing “more than half a billion words of fiction,” essentially copping to training its AI on illegally procured copyrighted material for the purpose of profit without the knowledge or consent of the authors.

Shaxpir and Prosecraft had both gone largely unnoticed since 2017. But on August 7, 2023, author and tech journalist Hari Kunzru found his books listed on Prosecraft and wrote a viral social media post that touched off a firestorm; within hours, the Author’s Guild had been flooded with hundreds of requests to issue cease-and-desist orders. By the end of the day, Smith, presumably acting on legal advice, had deleted Prosecraft from the web.

Shaxpir, though, remains operational at the time of this writing (although I won’t link to it for ethical reasons). It seems counterintuitive that the free site built on stolen content should be shuttered while the profit-making venture continues, but from a copyright-law perspective, there’s a clear complaint against Prosecraft, which actually reproduced brief excerpts of published works, whereas Shaxpir’s behind-the-scenes use of copyrighted material is still a legal gray area. Prohibition or permission to use something as training fodder for a large-language model is still granted on a case-by-case basis in the contracts or licenses for individual works. So-called “shadow libraries,” operating on the fringes of copyright law, will likely continue to take advantage of this ambiguity until regulations are amended to account for these new technologies.

But what about the promise of the product itself? Prosecraft and Shaxpir surely will not be the last websites to offer, by fair means or foul, objective metrics for the directness and zest of your writing. Is such a thing even feasible? How might it work? We’ll take a deeper dive into attempts to quantify “good writing” in the next edition of this blog, sixty days from now. See you then!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!