One of the cool things about being an editor is that you get to hang out with other word nerds and complain about pet peeves and disturbing trends in bad grammar. We’ve talked about several here, such as the following:

So let’s turn now to some more grammar sloppiness that gets under my professional skin: throwing em dashes around.

What’s an Em Dash?

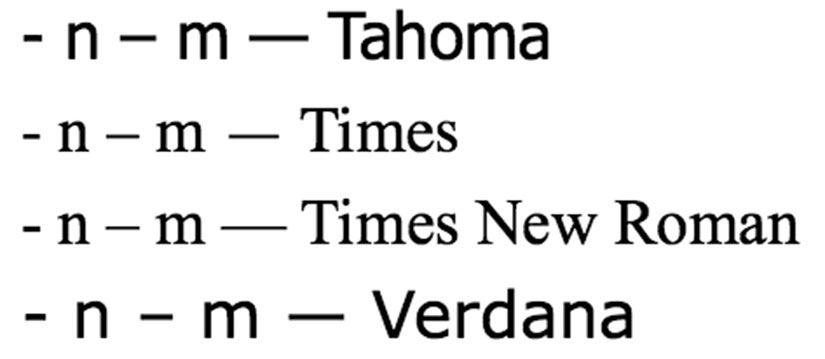

Dashes come in two sizes: – (en dash) and — (em dash). (The terminology goes back to typesetting. The first dash takes up the space of an “N,” and the second takes up the longer space of an “M.”) In Word, you can make an en dash by holding down the Ctrl key and pressing the minus/hyphen key on the numeric keypad and an em dash by holding down the Ctrl and Alt keys and the minus/hyphen key. You can also use Insert Symbol.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

The en dash is used mostly for number ranges (e.g., 1928–1972) and in some stylebooks to suggest a hierarchical or interactive relationship between two nouns (e.g., father–son relationship). Except when people use an en dash when they want to us an em dash, writers tend to use en dashes properly. It’s em dashes that get abused.

The em dash is the strongest punctuation we have in English for an interruption. It’s meant to represent a real change in thought or direction. It’s a break in the sentence, such as when someone is speaking and has a sudden, unconnected thought.

Ex: “But I know I gave the necklace to my sister,” she said. “She would never—Oh, no! I’ve been shot!”

Other nuanced punctuation for other types of interruptions include, in no particular order, the comma, the colon, parenthesis, and ellipsis. (Note that periods indicate the end of a sentence, not an interruption to the sentence.)

So What’s the Problem?

The problem is that, increasingly, people are using em dashes for all manner of interruptions.

Ex. (wrong): Nicholas—the boy I told you about—is coming to my party.

Ex. (right): Nicholas, the boy I told you about, is coming to my party.

“The boy I told you about” is a dependent clause and thus needs simple commas to be set off.

Ex. (wrong): I need a lot of things from you—loyalty, patriotism, and your undivided attention.

Ex. (right): I need a lot of things from you: loyalty, patriotism, and your undivided attention.

The colon here indicates that a list is coming to give examples of what is being talked about. There is no interruption of thought, only a change from a full statement to examples without having to say, “for example.”

Ex. (wrong): Several celebrities—I’m sure we all know who—are jerks in person.

Ex. (right): Several celebrities (I’m sure we all know who.) are jerks in person.

“I’m sure we all know who” is not an interruption; it’s an aside, or a little comment about the main sentence. It goes in parentheses.

Ex. (wrong): “I thought I told you to be careful,” he said. “I was—worried.”

Ex. (right): “I thought I told you to be careful,” he said. “I was . . . worried.”

Here, the ellipsis indicates that the speaker pauses, but not to change or interrupt the sentence. It’s a hesitation.

Throwing em dashes into a sentence whenever there is some sort of break muddies your meaning by ignoring the differences in the types of pauses we make.

Let’s Watch a Good Writer Do It Right

Here’s a bit of The Stand, by Stephen King, with all interruptions replaced by em dashes:

Stuart Redman—who was perhaps the quietest man in Arnette—was sitting in one of the cracked plastic Woolco chairs—a can of Pabst in his hand—looking out the big service station window at Number 93. Stu knew about poor. He had grown up that way right here in town—the son of a dentist who had died when Stu was seven—leaving his wife and two other children besides Stu.

Notice how an extremely simple paragraph that introduces us to the main character is all chopped up by those dashes. The em dashes ruin the flow and call attention to themselves. The original reads much better with its simple commas and matches the concept that Stu is “quiet”:

Stuart Redman, who was perhaps the quietest man in Arnette, was sitting in one of the cracked plastic Woolco chairs, a can of Pabst in his hand, looking out the big service station window at Number 93. Stu knew about poor. He had grown up that way right here in town, the son of a dentist who had died when Stu was seven, leaving his wife and two other children besides Stu.

***

A few paragraphs later, King uses an em dash the way it should be used. The guys are sitting around at a gas station talking about nothing when Stu sees a car careening toward the pumps:

“So I say with more money in circulation you’d be—”

“Better turn off your pumps, Hap,” Stu said mildly.

“The pumps? What?”

Norm Bruett had turned to look out the window. “Christ on a pony,” he said.

Stu got out of his chair, leaned over Tommy Wannamaker and Hank Carmichael, and flicked off all eight switches at once, four with each hand.

***

Note that the em dash breaks into someone else’s conversation, so we understand that although Stu’s tone is “mild,” his message is urgent. In fact, that one em dash signals that the entire scene is changing from some good ole boys shooting the breeze to a car crash (and all the horrible things that will follow).

(Yes, that last bit was an aside. So is this!)

The rule here is simply to remember that em dashes are powerful. They’re meant to be used when leaving one thought or action for another, not to set off some words for an explanation, a comment, or a deep breath. Please use them sparingly.

Julia H.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!