The last time I wrote in this space, I talked a little about formula fiction, both its appeal to readers and the mechanics of writing it. The academia has always looked down on this sort of stuff, which had its heyday in the pulp magazines of the early to mid-twentieth century and survives today in mass-market drugstore paperbacks, but it remains a source of modest, reliable pleasure, serving up solid genre entertainment with a minimum of artistic pretense. There’s nothing dishonorable in that.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

So what if these books and stories aren’t masterpieces for the ages? They were never meant to be; they’re disposable by design, written quickly and in great volume, and meant to be consumed in the same way.

Speed is the key. Formula fiction works best when it works fast, snagging the audience’s attention immediately and pulling us through the story with irresistible momentum. One of the masters of the form was Lester Dent, the Missouri-born author who came to prominence in the 1930s, writing most of the Doc Savage adventures (as “Kenneth Robeson”) along with countless other stories under his own name and a host of other pseudonyms. In almost thirty years in the business, Dent sent tens of thousands of words flying out the door every single month, using a formula that he called his “master plot.”

Dent began his writing process by defining four key story elements. In Dent’s article Dent explaining the master plot, he defined them as “a different murder method for the villain to use, a different thing for the villain to be seeking, a different locale, [and] a menace which is to hang like a cloud over the hero.” Dent, we must remember, was writing strictly in the action-adventure genre, and his tales often centered around opposing forces searching for some treasure; this setup that underpins everything from the classic The Maltese Falcon to the mutli-billion-dollar Avenger’s Endgame.

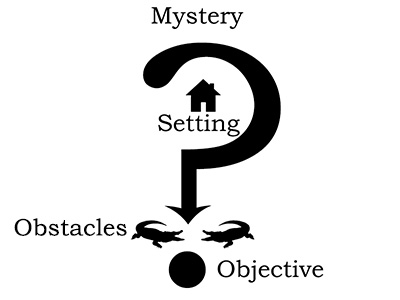

Not every story needs a murder, of course, or even a “villain” as such. But if we view Dent’s plot elements in more abstract terms, the schema becomes more flexible than it first appears. We might fairly rename them:

Hm, this looks a little like our old friend the MICE ratio, doesn’t it? The unique setting is the milieu; the mystery to be solved is the idea that powers the story; the obstacles your protagonist encounters are events arrayed against them. Objective doesn’t align precisely with character, but plot goals are intimately connected with a character’s desires.

Every plot can be reduced to, “A character wants something and either gets it or doesn’t.” Within that framework, what the character wants will depend on who that character is, even in genres like romance, where the objectives (love and marriage) are more or less predefined.

But that’s okay. Not every one of these four elements has to be unique. As Dent himself observed, “One of these different things would be nice, two better, three swell.” So if you’re writing romance, it’s fine to have “happily ever after” as the ultimate objective for your story, so long as you switch up the other three elements to make the story hooky and interesting.

From there, we start asking ourselves questions. Who are our characters? Let’s make the hero a newcomer to the community,say, a veterinarian who’s just joined the support staff, tending to the health of the animal athletes. Doc is smart, sensitive, and immediately smitten with the beautiful trick-rider Bonnie. Maybe Bonnie is a young widow. What happened to her husband? Ah, there’s our mystery.

BTW, did you know ProofreadingPal will work with you through all stages of your novel?

Just for fun, let’s try using this master plot to come up with a hook for a romance. Start with a unique setting. Western ranches are a popular background for blooming attraction; but how about the rodeo circuit? Combining the familiar beats of a cowboy love story with the world of professional sports entertainment could give us something that feels fresh.

We’re beginning to see the outlines of a plot here. Doc must overcome the suspicions of the tight-knit rodeo crew to get close to Bonnie (there’s our obstacle—one of them, anyway); but she holds him at arm’s length, seemingly afraid to become too deeply involved.

This isn’t a story, not yet. But we’ve got the ingredients of one, like the notes of a simple tune, a theme that a composer can develop into a multi-movement symphony. The rest of Dent’s formula addresses the structure and development of these ideas into a complete plot outline. We’ll pick up on the tale of Doc and Bonnie in two months’ time, when we complete our look at the pulp master plot. See you then!

Jack F.

Meanwhile, did you know ProofreadingPal offers free samples?

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!