Read Part 1 in this series about the Pulp Master Plot. Read Part 2.

Today, we continue our exploration of the “master plot” that helped writers of the pulp magazine era, like Doc Savage mainstay Lester Dent, produce compulsively readable adventure fiction with such incredible volume and speed. As always, we’re looking for strategies we can apply to writing contemporary genre fiction.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Last time, we looked at the four key story elements in Lester Dent’s pulp master plot: a mystery, an objective, a setting, and a set of obstacles. The genre may place some limitations on these elements—the objective in a romance will always be a happily-ever-after, the setting of a western will always be circumscribed in time and place—but originality in one or more of these elements will make for a livelier story.

As an example, we proposed a romance (there’s the objective) set in the world of a traveling rodeo (setting). Doc, a veterinarian who’s new to the show, falls for Bonnie, a widowed trick-rider and horse trainer. He must overcome the opposition of Bonnie’s work family (obstacles) to be with her, but though Bonnie plainly loves Doc, she keeps her distance, tormented by some secret shame (mystery). With these story elements in place, it’s time to outline the plot.

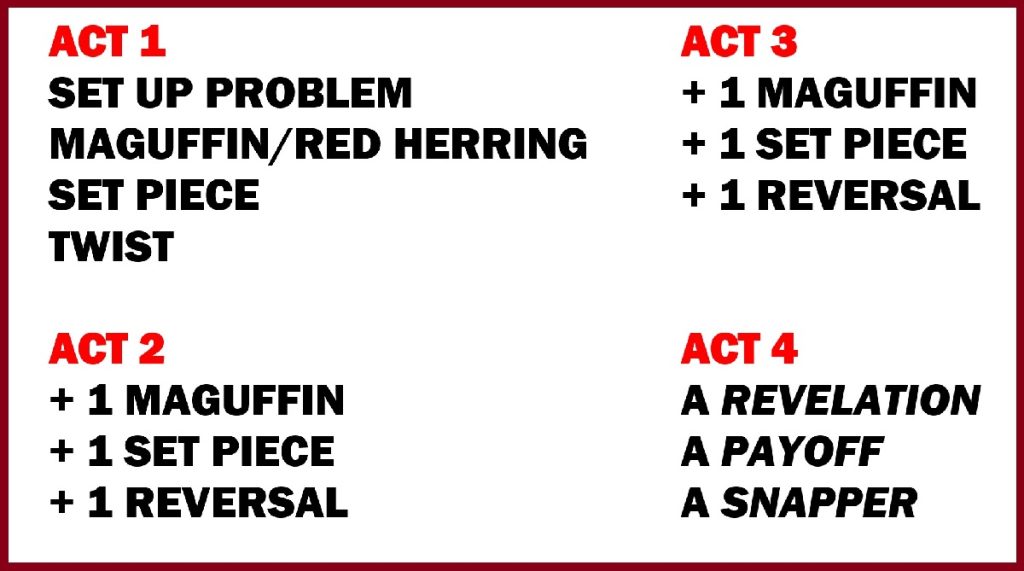

Structurally, Dent thought in fours. Starting with a word count in mind, he divided the story into quarters (acts) each with its own rising action and climax. I have a version of the formula pinned up in my workspace:

Let’s unpack my cryptic shorthand.

Act 1 introduces the characters and setting as economically as possible and sets up the central objective, mystery, and obstacles. Near the end of the act comes what I call a “set piece,” a term borrowed from film-making for any spectacular sequence, originally a scene (in the early days of film, a musical number) that would require the building of a special set. Put crudely, set pieces are “the good parts,” the must-haves that you come to expect when you read a particular genre. In Dent’s adventure tales, this would be a fight or a chase. In a whodunnit, it’s the uncovering of a major clue; in a horror story, a killing; in a romance, a love scene.

The payoff to a given set piece might be minor, but it should accomplish something. That breathless chase sequence may not end with capturing the bad guy, but the heroes should at least learn something worth knowing.

But they might not have time to enjoy it because we follow up the set piece with a twist, a surprise that deepens the central mystery, or an unforeseen difficulty, to end the act.

With the plot in motion, Act 2 keeps things moving. The heroes continue to pursue the objective; along the way, there’s another obstacle, an information reveal of indeterminate value, another set piece, and another reversal of fortune. Act 3 hits the same beats of another puzzle piece, another punch-up or make-out session, another setback, but with escalating stakes.

Act 4 brings the whole thing to a climax with a major obstacle, a solution to the mystery, and a final twist to bring the story to an exciting finish for rave reviews.

With the four-act structure in place, outlining your story is a breeze. Start with a word count or page count, break each act into chapters of equal length, and start placing your plot beats. Let’s say you go with six chapters per act, twenty-four in total. Introduce your characters and establish the baseline situation in Chapter 1. Various complications arise in Chapters 2 and 3, 7 and 8, 13 and 14; set pieces arrive in Chapters 4, 10, 16, and 22, wrapping up in 5, 11, 17, and 23, with twists in Chapters 6, 12, and 18, and so on down the line.

This method simplifies storytelling by eliminating the chance of going down a blind alley. Even if you start with only a few elements in place, a set piece or two, a mystery, an idea for an ending, you can see the landmarks on your journey. Filling in the blanks in the outline isn’t quite like connecting the dots in a children’s puzzle. It’s more like doing a crossword; the more spots you fill in, the more sense it all makes, and the more easily you can see where to go next.

Once you’ve got a chapter-level outline, keep drilling down. Subdivide each chapter into scenes or individual actions, simply relating the events of the story: “This happens, then this happens.” You’re planting signposts for yourself to follow along the road. Get as granular as you want; you needn’t have a bullet point for every paragraph, but it might be good to have goal for every thousand words, or even (if your story is intricately plotted) for every page. Working out your pacing in this “prewriting” stage—a misnomer, because really, it’s all writing—will keep you on track in the sentence-by-sentence part of the process.

(Don’t forget to schedule a break in there for some time with your editor!)

Next time, we’ll show the formula in action, as we develop our rodeo romance of Doc and Bonnie into a working outline. See you then!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!