One way you can tell I’m an insufferable nerd is that I celebrate Burns Night. Every January 25, pandemic permitting, I gather with friends and strangers to sip whisky, eat haggis (or a reasonable approximation), and celebrate the literary legacy of Robert Burns (1759–1796), Scotland’s greatest poet. You’ve heard Burns’s work, even if you don’t realize it; he wrote the words to “Auld Lang Syne,” one of the most familiar songs in the English language.

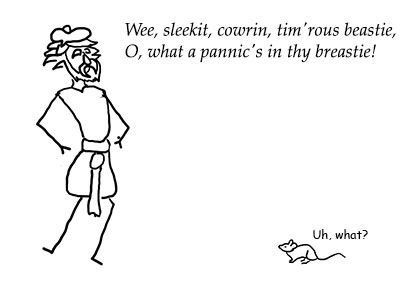

Except that it’s not in English, exactly. Burns wrote in what he called Lallans, today called Lowlands Scots, which is still spoken by more than a million people in Scotland. And what’s Lallans, exactly? Let’s look at the opening stanza of the poet’s “Address to a Haggis,” traditionally recited at every Burns Night supper.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace

As lang’s my arm.

The grammar and much of the vocabulary are recognizably English-adjacent, and those last two lines, archaic spelling aside, are quite intelligible: “Well are you worthy of a grace/As long as my arm.” Lallans, though clearly not Modern English, shares with it a common ancestor: the Middle English of The Canterbury Tales. The UN classifies Lowlands Scots as a distinct tongue, indigenous to Scotland; a West Germanic language derived from Early Middle English, and thus a “sister language” to Modern English, from which it began diverging around 1150 CE.

ProofreadingPal, of course, provides editing services in a number of regional English varieties (e.g., US, UK, Canadian English), but we don’t edit Lowlands Scots. Neither is it among the languages handled by our sister agency TranslationPal. (More’s the pity.) So what does the poetry of Burns have to do with writing and editing in Modern Standard English?

For writers of fiction, the answer is “plenty.” Burns’s great contribution was bringing Lallans to prominence as a written language, rather than a spoken vernacular. And the strategies he used to do it can teach us a lot about writing dialogue, particularly dialogue in dialect.

Linguistic Dialects and a Warning to the Unwary

When we talk about dialect in fiction writing, we’re using the term rather differently from its meaning in academic linguistics, where it refers to a variety of a specific language used among a particular population. When linguists talk about “the Sicilian dialect,” for instance, they’re talking about distinct form of Italian native to Sicily and spoken nowhere else in Italy. There’s no consensus in the field of what constitutes a dialect as opposed to a separate language; Norwegian and Danish, for example, are officially different tongues even though they are mutually intelligible, but there’s also more to a dialect than a funny accent and some nonstandard grammar.

There’s nothing makeshift, for instance, about real-world English dialects and creoles like African-American Vernacular English (sometimes formerly called “Ebonics”) or Jamaican Patois. Their rules are no less complex than those of Standard English, and they are no less nuanced or expressive; indeed, in some respects (e.g., Ebonics’ “habitual be” formation), they can convey subtleties of meaning that Standard English cannot match. And their form is highly contextual; their use by an individual speaker will vary according to the setting and the audience.

White writers sometimes attempt an approximation of Ebonics when writing dialogue for Black characters, usually with disastrous results. Ebonics is not simply “broken English,” but functionally a language in its own right. If you haven’t made an extensive study, you shouldn’t attempt it any more than you’d try writing pages of dialogue in French simply because you’d seen a few foreign movies and “know how they talk.”

Dialect in Fiction

Literary (as opposed to linguistic) dialect comprises a set of tools for conveying the flavor of a character’s speech. This may include the use of nonstandard vocabulary, such as slang or jargon, or favorite idiomatic expressions. This is an obvious feature of Burns’s literary Lallans, which freely employs regional terms like sonsie, meaning plump or rounded. Regionalisms in American English may not be quite so indecipherable; but it tells us something about your character whether he drinks soda on the stoop or pop on the porch.

Another feature of literary dialect also found in Burns’s poetry is phonetic spelling. Using” a’,” “weel,” and “aboon” in place of “all,” “well,” and “above” gives non-Scots an inkling of the sound of spoken Lallans, bringing it to life in the mind’s ear.

Similarly, spelling words phonetically is useful for rendering American regional accents. “Geddouttahere! Dat ain’t how da woid is spelt!” places us in very different location than does “Ah’m just a simple country lawyuh, suh.”

One mustn’t overdo it, of course, but many instances of phonetic spelling have gained widespread use, and using them judiciously can help make characters and their speech believable. There’s a subtle difference between “Give me a cigarette, would you?” and “Gimme a cigarette, wouldja?” not just in sound, but also in affect, and in what each tells us about the character.

A peculiar subset of phonetic spelling is focused entirely on character. “Eye dialect” is the phonetic rendering of more-or-less standard pronunciation. Consider the sentence, “That fella wuz talkin’ t’ Missus Jones.” When read aloud, it’s indistinguishable from the same sentence written with standard spelling. But to the eye, it suggests something about the speaker and their relationship with language. It’s not so much about how they sound, but about something internal: a lack of formal education or even illiteracy. Like all the tools of literary dialect, it forces us to pay attention to the dialogue by touching everyday speech with strangeness.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your English document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your English document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!