We’ve devoted several blog entries to the perils of poetic language, particularly how figures of speech can detract from the clarity of your prose. These warnings might have left you with the impression that the stuff of poetry is incompatible with good writing.

But poetry is simply a way of thinking about language, a theory that words can be arranged for beauty as well as for meaning. There is no reason why even modest explanatory prose cannot be a pleasure to read. And it is beauty—or panache, or style, whatever you want to call it—that gives prose its pleasure, distinguishing memorable writing from that which is merely functional.

Meter? I Hardly Knew Her!

Over the next few months, we’ll rummage through the poet’s toolbox and discuss using the methods of verse to give your informational writing a touch of music.

To begin, I’m going take ten minutes to teach you the basics of prosody, which is just a fancy word for the study of meter (i.e., the rhythmic organization of words). Meter is the foremost quality separating that which is poetry from that which is not. Consider Shakespeare. His blank verse runs for long stretches without a rhyme in sight, but the pulse of the language gives it an irresistible forward momentum such that actors can memorize and deliver dozens or hundreds of lines and never get a word wrong. That’s memorable writing.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Feet, Don’t Fail Me Now

Rhythm, whether in drums or in poetry, is a matter of strong beats and weak beats. We determine the meter of a poem by counting the stressed syllables in a given line. Let’s begin with an example from Shakespeare, then work our way backwards to general principles. Look at this famous line from Romeo and Juliet:

But soft! What light through yonder window breaks? (III, ii, 2)

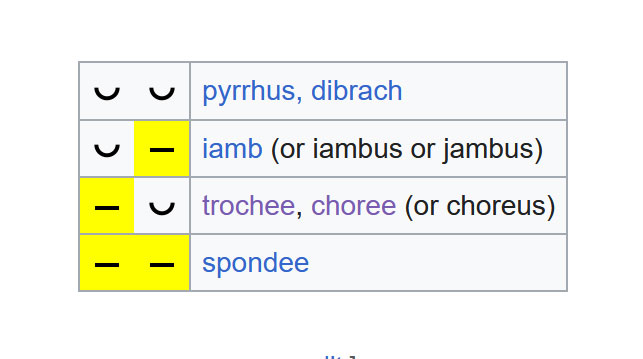

Breaking that line down, we see five stressed syllables (also called accents). More than that, though, we see a pattern of stresses, five groupings, each consisting of a weak beat followed by a strong beat (which is called an iamb).

but SOFT | what LIGHT | through YON | der WIN | dow BREAKS

In the study of prosody, these grouping are called “feet.” Each foot is a distinct unit consisting of one stressed syllable and one or more unstressed syllables. In Shakespeare’s case, there are usually five unstressed/stressed feet to make five iambs in any given line. (As five = pent, it’s called iambic pentameter.)

In the study of prosody, these grouping are called “feet.” Each foot is a distinct unit consisting of one stressed syllable and one or more unstressed syllables. In Shakespeare’s case, there are usually five unstressed/stressed feet to make five iambs in any given line. (As five = pent, it’s called iambic pentameter.)

Each possible grouping of stressed and unstressed syllables has its own name. A trochee, for instance, consists of two syllables, with the stress on the first. Wander, call me, downbeat, hit it: these words and phrases are all trochees. An anapest is three syllables, with the stress on the last: violin, by the sea, any time, minuet. A spondee is made up of two syllables with roughly equal stress: football, tough guy, downtown, bobsled.

Playing by Ear

Dr. Seuss, by contrast, used anapestic tetrameter—four feet per line, each consisting of two unstressed syllables followed by a stress—in some of his most famous works. Look at where the beats fall in these opening lines from How the Grinch Stole Christmas:

ev’ ry WHO | down in WHO | ville liked CHRIST | mas a LOT

but the GRINCH | who lived JUST | north of WHO | ville did NOT

The triple meter gives the lines a swing, a jazziness quite different from the stately cadence of Shakespeare.

And it’s the swing that’s important here. The study of prosody can be intimidating for beginners. There are a lot of names to memorize. But you can use the tools of meter even without knowing their names, just as a musician might play by ear. It’s a matter of pattern recognition—of scanning a poem or passage of prose and thinking, “Oh, there’s a part here that goes OOM-pah-pah, OOM-pah-pah.” These things all have names—and I encourage you to learn those names—but understanding the way a meter feels is far more important than knowing what it’s called.

My ten minutes is up now, and we’ve walked through the theory. We’ll talk next time about the practical side of writing for rhythm. See you then!

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!