Many writing styles and teachers frown on the overt use of rhythmic devices and varieties of rhyme in serious writing on the grounds that they’re frivolous, or distract from the informational aspect of a project; we have shown how using these elements in subtle, tasteful ways can make even straight prose more memorable.

Now consider another aspect of poetry often discouraged in formal writing: what the APA Publication Manual rather vaguely calls “figurative language.” The APA website clarifies things, cautioning against “language in which meaning is extended by analogy, metaphor, or personification or emphasized by such devices as antithesis, alliteration, and so forth.”

We’ve talked about the need to be careful when using personification (or, more properly, anthropomorphism) and alliteration and other varieties of rhyme, but it seems odd to list analogy and metaphor as two separate phenomena, when in fact the latter is a subset of the former.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. What is analogy, anyway, and why should you avoid it in formal writing? Simply put, analogy means describing one thing in terms of another, either by comparison (pointing out similarities) or contrast (pointing out differences). Analogy forms the basis for many idiomatic expressions. Overreliance on idiom can muddy of your prose, and that’s reason enough to be wary: Clarity, remember, is Job One for informational writing. But the varieties of analogy are thoroughly woven into our everyday speech, in expressions and constructions that are absolutely clear to native speakers. Indeed, it’s sometimes impossible to be clear without using an analogy.

A comparison, for instance, is a form of analogy. Consider this statement: “The Unity statue in Gujarat, India—the world’s tallest—stands 597 feet, about twice the height of the Statue of Liberty.” We are describing one thing (the Statue of Unity) in terms of another (the Statue of Liberty). Assuming we are writing for a US-based audience who will be more familiar with the latter, the comparison is essential for comprehension.

The two varieties of analogy you might remember from grammar school are simile and metaphor. In a simile, the comparison is made explicit, often (though not always) through the use of the words “like” or “as.”

The waves crashed like thunder.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

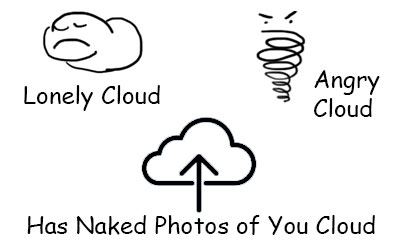

I wandered lonely as a cloud.

Metaphor, by contrast, leaves the comparison implicit: “The road was a ribbon of moonlight.”

Of the two, metaphor seems at first blush more “poetic,” more fanciful; in practical terms, you can’t make a ribbon from moonlight, and even if you could, you couldn’t drive on it. A simile reassures us that we’re not meant to take it literally. It’s not that the waves are thunder; they simply sound similar. So you’d think that similes, carefully controlled and qualified, would be more acceptable in informational writing.

Of the two, metaphor seems at first blush more “poetic,” more fanciful; in practical terms, you can’t make a ribbon from moonlight, and even if you could, you couldn’t drive on it. A simile reassures us that we’re not meant to take it literally. It’s not that the waves are thunder; they simply sound similar. So you’d think that similes, carefully controlled and qualified, would be more acceptable in informational writing.

But that’s not always the case. Some analogies are so common that we’ve nearly forgotten their origins as such. If you wrote, for instance, “Warren Buffet’s stature among financiers is akin to that of a titan, one of the primordial giants of Greek myth,” your editor would reach for the red pencil. Rendering the image as a simile, while more literally accurate, makes the image seem bizarre. But metaphorically call him “a titan of finance,” and no one blinks an eye.

And because the meanings of words sometimes change, analogous phrases can become literal with time. For instance, the word “genius,” when applied to someone of intelligence or skill, began as a metaphor. The word, related to “genie,” referred to a magical, invisible spirit of Roman myth, sort of a cross between a muse and a guardian angel, who hovered near great craftsmen and helped them with their work. People would say of a great artist, “He has a genius for painting,” meaning that he had an otherworldly assistant guiding his brush. When the word was first applied to the painter himself, it was used metaphorically to imply that his skill was nigh-supernatural; in time, the metaphorical meaning crowded out the literal one.

Metaphor or not, though, the meaning is immediately clear. And as with most writing rules, the guidebooks’ prohibition on colorful language is really just a plea for clarity. Used sparingly, in commonly understood expressions or for illustrative purposes, simile and metaphor can make your prose more understandable and memorable.

Jack F.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

Get a free sample proofread and edit for your document.

Two professional proofreaders will proofread and edit your document.

We will get your free sample back in three to six hours!